Animal categories determine their worth.

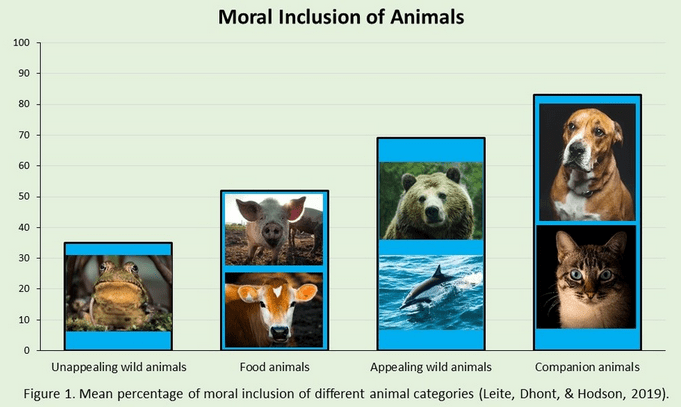

People have a paradoxical relation towards animals. Some are valued as family members (pets), others, especially farm animals, are exploited in a dreadful manner. This paradoxical relation is often reffered to as the meat paradox1. Other relevant categories are appealing wild animals, which are human-like (e.g. chimpanzees), or are known for being intelligent (e.g. dolphins) and therefore of moral weight for many people, and unappealing wild animals (e.g. snakes, or snails), which can trigger negative emotional reactions (such as fear or disgust) and are therefore morally devalued2.

Just by telling a person, that a specific animal they didn’t know about earlier is „edible“, these people attribute less moral worth to it 3. So it’s not just that people rank animals according to their e.g. cognitive capacities, but rather the categories we grow up with determine an animals worth – even if it is such an arbitrary one as „edible“.

Human Supremacy Beliefs.

In the realm of human intergroup relations there is one main psychological construct that explains the exploitation and moral exclusion of different minorities, and by that shows a strong overlap between racism, sexism, etc.: social dominance orientation.

People with a high social dominance orientation tend to think in groups and in these groups‘ struggle for status and moral consideration. Racism and sexism e.g. thus are means of oppressing minorities, which are deviant from a majority-perspective. The Oppression enables the majority to maintain the status quo 4.

In the realm of human-animal relations, social dominance orientation also showed to be the best explanation of speciecism, which lines up with the connection to racism and sexism. An even stronger predictor of different outcomes regarding animal exploitation are human supremacy beliefs. These are beliefs about the gap in status between humans, and nonhuman animals. So people with high human supremacy beliefs think of humans as inherently „higher“ than other animals 5.

Higher human supremacy beliefs are accompanied by higher meat consumption as well as a higher support for animal exploitation practices 5. If this hierarchical human-animal-divide is experimentally lowered (by focusing on the „human-likeness“ of some animals), moral inclusion of these animals, lower speciecism and even more prosocial attitudes towards human minorities result 6. Just like social dominance orientation, human supremacy beliefs are related to conventionalism, and thus to our next construct: the vegetarian threat.

Being threatened by vegetarianism.

Conventionalism, and a desire to cling to the status quo, is highly related to social dominance orientation and human supremacy beliefs. In the realm of environmentalism, studies were able to show, that people who thought environmentalists would threaten the Western way of life, show less support for climate-friendly policies as well as stronger denial of climate change itself. Environmental threat thus leads to a pushback effect against the climate itself 7.

Vegetarianism as a different progressive movement, could therefore also trigger pushback effects. Exactly this question was examined by Leite, Dhont and Hodson 2. The researchers were able to show that human supremacy beliefs and a perceived vegetarian threat causally lead to more speciecism, higher meat consumption and higher moral exclusion of different animals. Interestingly human supremacy beliefs as a general attitude towards animals led to the exclusion of all animals, but the vegetarian threat led to the exclusion of mainly farm animals – so it is a pushback effect, which targets the relationship that is questioned by vegetarians.

Paradoxically, the rise of vegetarianism can lead people with these conventionalist attitudes to lower their moral consideration of the animals in question. A more fine-grained understanding will be necassary for taking countermeasures to this kind of pushback.

Sources

1 Gradidge, S., Zawisza, M., Harvey, A. J., & McDermott, D. T. (2021). A Structured Literature Review of the Meat Paradox. Social Psychological Bulletin, 16(3), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.32872/spb.5953

2 Leite, A.C., Dhont, K., & Hodson, G. (2018). Longitudinal effects of human supremacy beliefs and Vegetarianism Threat on Moral Exclusion (vs. Inclusion) of Animals. European Journal of Social Psychology, 49(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2497

3 Bratanova, B., Loughnan, S., & Bastian, B. (2011). The effect of categorization as food on the perceived moral standing of animals. Appetite, 57(1), 193-196. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.04.020

4 Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

5 Dhont, K., & Hodson, G. (2014). Why do right-wing adherents engage in more animal exploitation and meat consumption? Personality and Individual Differences, 64, 12-17. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.02.002

6 Bastian, B., Costello, K., Loughnan, S., & Hodson, G. (2012). When closing the human-animal divide expands moral concern: The importance of framing. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 421-429. doi: 10.1177/1948550611425106

7 Hoffarth, M.R., & Hodson, G. (2016). Green on the outside, red on the inside: Perceived environmentalist threat as a factor explaining political polarization of climate change. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 40-49. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.11.002